Advancing Computational Psychiatry by Linking Theory to Practice

I chose to review Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications by Quentin Huys et.al. (2016). This paper introduces the emerging science of computational psychiatry, examines its two approaches, and reviews advances in both methodologies, with an emphasis on clinical applications. This paper argues that combining both theory- and data- driven approaches are very promising in advancing the field of psychiatry.

What is computational psychiatry?#

Huys et.al. defines computational psychiatry as the application of ‘multiple levels and types of computation on multiple types of psychiatric data in an effort to improve understanding, prediction, and treatment of mental illness’. This is a very compact definition of the rising field, so let’s dissect it!

Why multiple levels of computation?#

One of the main things that complicate psychiatry is that mental health depends not only on the function of the brain (the most complex organ in living organisms we know so far), but also how that function relates to, influences, and is influenced by the individual’s environmental and experiential challenges. Understanding mental health, and its disruption, therefore relies on bridging multiple interacting levels, from molecules to cells, neural circuits, cognition, behavior, and the physical and social environment.

What makes psychiatry even difficult is that the mapping between these levels is not one-to-one. The same biological disturbance can affect several seemingly unrelated psychological functions and, conversely, different biological dysfunctions can produce similar psychological and even neural-circuit disturbances. For example, as stated by Jon Roiser of University College London in this lecture, symptoms such as anhedonia (loss of interest and inability to feel pleasure) appear in multiple disorders such as major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease. This makes the diagnosis and choice of treatment for patients a hard process for clinical psychiatrists.

Why multiple types of psychiatric data?#

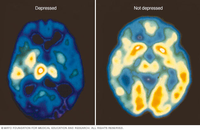

|

|---|

| Figure 1. A PET scan comparing brain activity during periods of depression (left) with normal brain activity (right): a decrease of white and yellow colors, along with increased blue and green areas, indicates that depressed individuals have decreased brain activity.(Source) |

In order for psychiatrists to diagnose properly their patients, they use a wide range of psychiatric data, which maybe classified into either brain data (such as EEG, fMRI, and PET scans) or behavior data (such as HDRS and QIDS scores). These information gathered by clinicians are also the same data used in computational psychiatry.

These data are high-dimensional, which is both a blessing and a curse for computational psychiatry. The blessing of dimensionality is that in infinite-dimensional space, any finite-sized dataset can always be classified perfectly using a simple linear classifier. But this blessing can also be curse, as the addition of new features will increase the danger of overfitting—that is, the resulting model will generalize poorly to new data.

Why multiple types of computation?#

Computational psychiatry encompasses two approaches: data-driven and theory-driven models. The authors have delved a lot in reviewing the latest advances in both approaches. What exactly are these two approaches?

Data-driven approach#

This approach refers to the theoretically agnostic data-analysis methods from machine learning (ML) applied to psychiatry. This approach has started to show success in several clinically relevant problems, such as diagnostic classification, prediction of treatment response, treatment selection, and understanding relations between symptoms. This approach, however, is limited in its ability to capture the complexities of interacting variables in and across multiple levels. Studies aimed at developing clinically useful applications have tended to use a data-driven over a theory-driven approach.

Theory-driven approach#

This approach includes theory-driven models that mathematically specify mechanistically interpretable relations between variables—often including both observable variables and postulated, theoretically meaningful hidden variables). These models can be classified into one of these three types:

- synthetic models (e.g. biophysically realistic neural model)

- algorithmic models (e.g. reinforcement learning model)

- optimal models (e.g. Bayesian model)

While this approach has yielded key insights at many levels of analysis concerning the processes underlying psychiatric disorders, it has yet to be applied to clinical problems. Studies aimed at increasing understanding of disorders have tended to use a theory-driven over a data-driven approach.

A Bright Future for Computational Psychiatry#

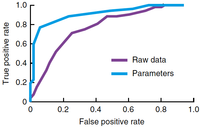

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Theory-driven models yield parameters that can be used as features to improve ML performance. A classifier trained on estimated parameters of a model fitted to simulated behavioral data (light blue curve, AUC 0.87) performed better than when trained on the raw data directly (purple curve, AUC 0.74). (Image and Description Source) |

We have seen the advantages and limitations of both data- and theory-driven approaches, yet a bright future still awaits for computational psychiatry, and this lies on the integration of these two approaches. Studies have already been conducted that show the promising advantage of combining the two approaches (see Figure 2). Such a combination may solve the curse of dimensionality—theory-driven approach uses prior knowledge to massively reduce the dimensionality of the dataset by ‘projecting’ it to the space of a few relevant parameters. A data-driven approach can then work on this lower-dimensional dataset with increased efficiency and reliability.

Applying a computational perspective in understanding, diagnosing and treating mental illness poses a potential to revolutionize the field of psychiatry. It is my earnest hope that in the future, practicing clinicians may also fully embrace the utility of this computational approach to mental health.